The Military Doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)

If you like this piece and all of my past writings, please subscribe below or become a patron at patreon.com/ForwardBlog

What is MAD?

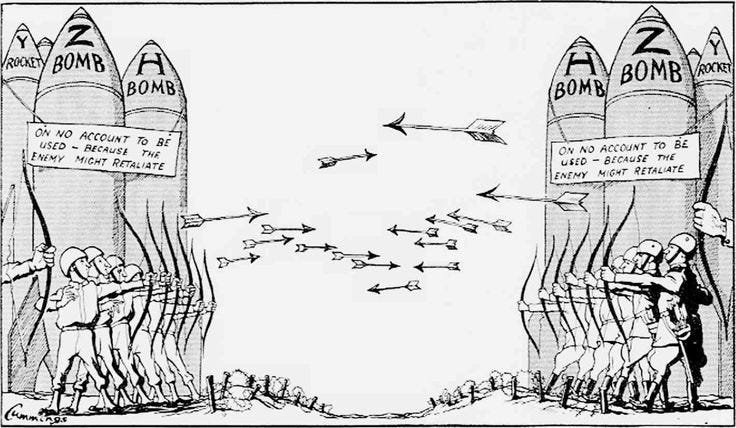

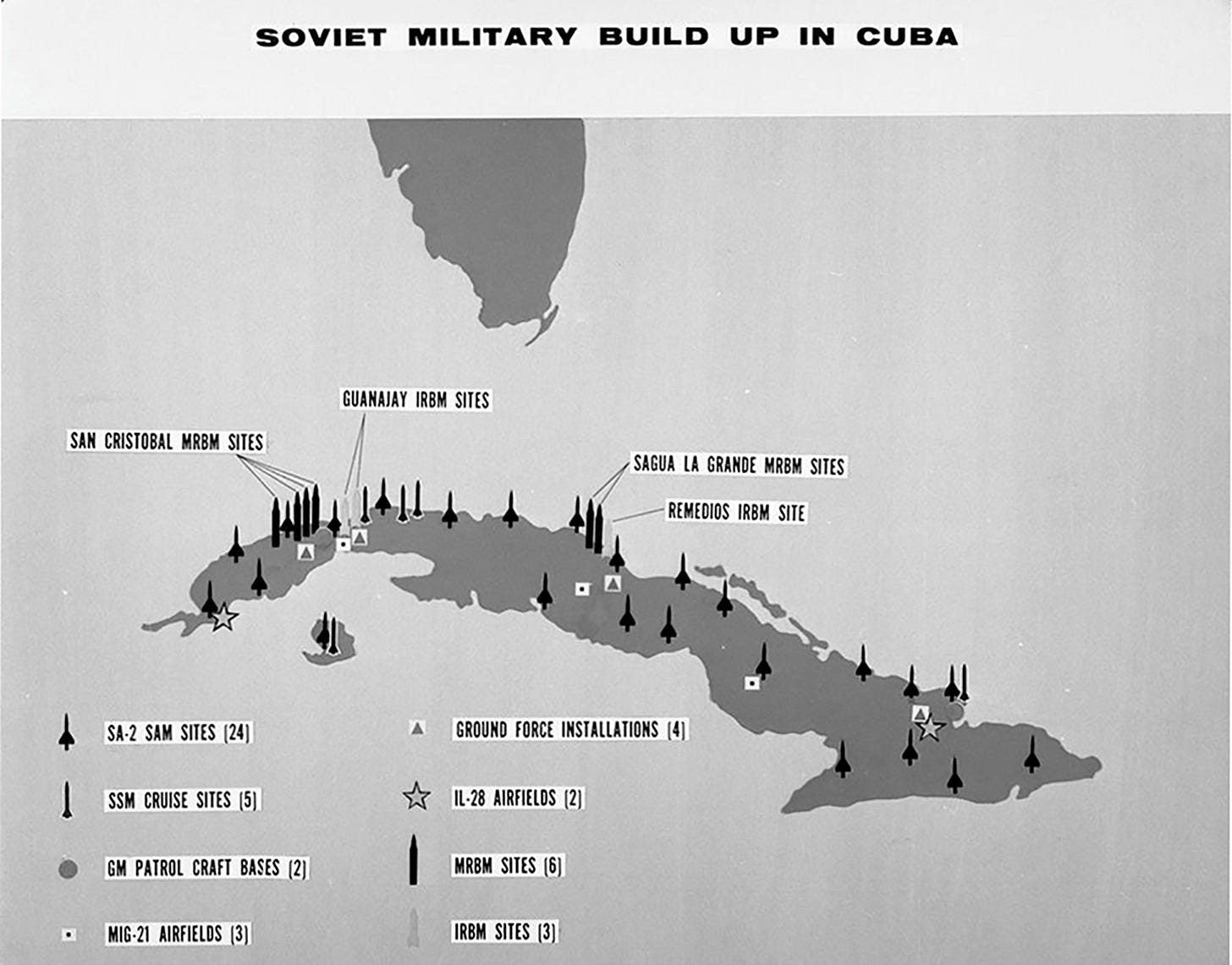

Mutually assured destruction or as it’s known by its acronym, MAD, is a doctrine of military strategy in which a full-scale usage of nuclear weapons by two or more opposing sides, would completely annihilate both the attacker and the defender. This would thus initiate a chain reaction in which other countries, both allies and enemies of the initial two, would engage with their nuclear weapons. This engagement would quite obviously destroy the world as we know it by making the earth almost completely uninhabitable. The term was first coined in 1962 by Donald Brennan, a strategist at the Hudson Institute. It’s part of the “Nash equilibrium” game theory in which once armed, neither side has the incentive to initiate a conflict or disarm. This time period of world history during the Cold War was when tensions were at their most high between Washington and the USSR. Due to the seemingly endless proxy wars that the countries engaged in from 1945-1990, by 1962, it seemed obvious to everyone that the two countries were perilously close to a nuclear engagement. The Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis put everyone in the National Security Department on high alert. Khrushchev understood just as much as JFK, that MAD was a guarantee if Washington decided to do a full-scale military invasion of Cuba. Hence the decision by the CIA (without full knowledge by the White House) to fund a Miami-based cell of Cuban exiles and CIA agents whose goal was to make a small-scale marine landing in the Bay of Pigs, in which the end result would be a coup taking out Fidel Castro. CIA plans to overthrow the Castro government began in early 1960. The atmosphere that formed after JFK’s decision to withhold air support during the Bay of Pigs invasion and the subsequent embarrassment that the failed operation caused, are widely considered by many historians to be major motivating factors in the CIA’s likely involvement in his future assassination. The thirteen days of unbelievable tension during October of 1962 would later be called the “Cuban Missile Crisis” and it was the most dangerous time of all. It was also a direct and obvious path, once the embarrassment of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion settled in during late 1961 and early 1962. And as those who’ve read David Talbot’s book, The Devil’s Chessboard, Allen Dulles was no fan of JFK and the two men loathed each other. However, this is not a tale of JFK and the CIA’s power in the 1960’s. This is a piece about the formation of MAD and why this doctrine is important to understand and respect if you are going to be an international diplomat in today’s hyper-violent, inegalitarian and partisan world.

How Close They Came

Even the most hardline right-wingers in Washington at the time didn’t want nuclear conflict. Barry Goldwater may have kept hinting in public that he wanted nuclear conflict, but he didn’t actually mean it. As did nobody inside the Pentagon. How could America’s burgeoning corporations and elite capitalist class make any money if both countries destroyed each other through nuclear war? Both sides claimed to abide by MAD but there were two occasions where they came very close to nuclear war. The first was the Bay of Pigs invasion and the second was the Cuban Missile Crisis. During the crisis, a Soviet Navy officer named Vasili Arkhipov, was in a nuclear submarine and refused direct orders to use nuclear torpedos against the US Navy. He’s credited in Russia today with having played a major role through his one-time critical decision in that thirteen day period. In the US, barely a soul knows his name. He certainly is no hero who is taught in the public school textbooks. During the early 1960’s there were many times where the CIA left the State Department out of the loop on covert operations. This was of course always on purpose. Some of it was for legitimate reasons to provide the federal government with plausible deniability but most of it was just to conduct covert operations overseas and purposely undermine diplomatic measures. This process would be repeated over and over again throughout the next 30 years of the Cold War. Vincent Bevins highlights the dynamic well in his bestseller 2020 book, The Jakarta Method.

The Theory and How it’s Applied

Under the MAD doctrine, each nuclear power understands that they have enough weaponry to destroy each other. That’s the basics of the doctrine. Everything that comes in the theory from that point on, gets more complicated. For instance, the doctrine assumes that neither side (at the time only being the USSR and Washington), would even dare to launch a first strike because the other side would be programmed to launch on warning. This response then takes out the human element of decision making and props up the basic tenant of defense, which is automatic retaliation. The launch on warning is also called a “fail-deadly.” The surviving forces of the defending side would have to issue a “second strike” thus creating unacceptable losses for both countries. If you are punched in the face, you will respond with an equal or greater amount of force depending on your strength. The concept applied here at all times is basic deterrence. But behind closed doors, both sides would continue to harden the diversification of their delivery systems by building new silos, submarines and bombers. These aggressive methods would eventually calm down though and led to both parties signing the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty on May 26, 1972.

When Was MAD First Discussed?

The first time the concept was even discussed in national security circles was about 100 years before the Cold War even began. An English author named Wilkie Collins was writing about the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. The savagery and the unequal balance of power that led to the French defeat and concession of lands, caused him to write this; “I begin to believe in only one civilizing influence—the discovery one of these days of a destructive agent so terrible that war shall mean annihilation and men’s fears will force them to keep the peace.” As technology advanced into the 20th century, more writers were quoted referring to weapons of “mass destruction” capabilities. The inventor of the Gatling gun also had a similar quote even earlier, back in 1862 at the apex of the US Civil War. These early references would be repeated by members of Washington’s National Security apparatus a few times during WWII. Nazi Germany was on the move in both western and eastern Europe and over in the Pacific Theater, Japan was taking over entire islands in the western Pacific. Nuclear capability and development was in constant discussion. Nuclear physicist, Robert Oppenheimer (the developer of the Manhattan Project), knew very well how deadly these weapons were and even regretted his involvement in their creation. This way of thinking amongst nuclear physicists at the time became known as “Oppenheimer’s Dilemma.” Surely, even in the early days of WWII, physicists and governmental experts would have known that nuclear war would definitely annihilate an entire planet if there aren’t international limitations put on their deployment. By the time Truman’s administration actually dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, international observers were beginning to notice the aggressive nature taken by Washington’s National Security apparatus. Even Winston Churchill reportedly did not like the usage of nuclear weapons on innocent civilian populations (although ironically he had no problem with sending millions of Indians to their graves through starvation in 1943-1944). Our usage of these weapons in Japan is even more disgusting when you consider the fact that the Japanese Empire was unraveling at the time and not far off from surrender. However, because the Japanese Imperial Forces ignored the Potsdam declaration warning of surrender from the Allied forces, they supposedly deserved nuclear weapons being used on their mainland. Even historians today, regardless of bias, can agree that the use of nuclear weapons on Japan was totally inhumane and unnecessary. From the years of 1945-1955, there was a shift in where the discussions on MAD doctrine took place. Think tanks like the RAND corporation and the DoD agency named the “Strategic Air Command” were on the frontline in developing and deploying nuclear weaponry.

Second Strike and the Late Cold War Period

MAD is still used in doctrinal principles today. The military and our national security state are fully aware of the deadliness of nuclear weapons. Posturing has been a large part of the latter stages in the Cold War whereas in the early 1960’s there were real threats to world annihilation. The nuclear strategy of “second strike” was first developed by Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense in the JFK and LBJ administrations. McNamara was the one who fully declared MAD as a strategy in 1960. Out of that declaration came the second strike strategy, which was the operational capability of the US to retaliate with a nuclear attack at least as proportional to a hypothetical Soviet one. At this time in the early 1960’s the US had achieved an early form of second strike capability by fielding continual patrols of strategic nuclear bombers with a large number of planes always in the air and on their way to and from fail-safe points near the Soviet border. These were early techniques that served two purposes. One, to watch the border and collect recon intelligence. The second was to demonstrate to the Soviets that Washington could deploy mobile nuclear missiles that could easily reach Moscow. While this may seem aggressive (and it is), the Soviets practiced basic deterrence because they knew the US had the upper hand. However, it became too expensive for the DoD to keep planes in the air and thus a rush was placed on the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) as a way to close the “missile gap” and ensure a second strike would be guaranteed in the advent of nuclear war. By early 1959, ICBMs were already developed in the USSR and Washington was quickly closing the gap. As the 1960’s wore on, there was a de-emphasis on the usage of ICBMs and tensions began to ease a bit under the Nixon and Brezhnev administrations. By 1980, Jimmy Carter decided to amend the MAD doctrine with the adoption of the counterveiling strategy Directive 59. It basically stated instead of bombing the population in retaliatory nuclear strike, it would be best to bomb Moscow and the politburo and the Soviet leadership. It was a minor change and one that probably would have made no effective difference since there was clear de-escalation tactics being done by the Soviet leadership and they were busy in Afghanistan at the time. As Ronald Reagan came into office, things would stay the same. The administration didn’t amend MAD, they continued to abide by the doctrine but used other aggressive methods to put pressure on the Soviets that ended up undermining the purpose of MAD anyway. The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), which got the nickname “Star Wars”, was the continuation of MAD only with the typical over-the-top Reagan-era Hollywood spin. Reagan always needed to make it look like the world was in danger from Soviet bombs at all times and the best way to scare the population was to insert a little bit of flair into the MAD doctrine. Most Americans weren’t even aware of the doctrine and just wanted to assume that their government would keep them safe at all costs. Thatcher and other allies criticized the SDI, not just because it was totally unnecessary but because it undermined the “assured destruction” aspect required for MAD. Critics argued that the first strike capability was needed because the Soviets were always aggressors (this of course is not even close to true). In any event, the Cold War wound down in the late 1980’s largely due to the Soviets’ own mismanagement of their economy and over-extension of their military capabilities in Afghanistan. Their War in Afghanistan cost them dearly. It’s similar to ours in Vietnam. They lured us into spending millions of dollars and sacrificing thousands of lives in Vietnam in the 1960’s. And we lured them into doing the same in Afghanistan once the CIA started arming the Islamic fundamentalist Mujahideen rebels during almost the entirety of the war. These proxy conflicts certainly cost the Soviets more than it did the US. There are many reasons for that. But what is most important to take away here is that MAD doctrine persisted and thankfully might have saved the planet on more than one occasion. Let’s hope a level of common sense continues to prevail in the world order.